Gulls and Terns

Summer gulls: herring, greater black-backed and laughing gulls

Terns are quite different. These slim, fragile looking birds are quite specialized. Variously described as “sea swallows” or “flying scissors,” terns are built for maneuverability. Their long wings and forked tails give them flying abilities unmatched on Stellwagen. These are summer residents of the area, moving north in summer to take advantage of fish populations to feed their young in protected colonies. Superb plunge divers with excellent vision, terns can adjust the size of their prey to the size of their chicks: newly hatched chicks may be fed on herring fry and are slowly graduated to adult sand lance. After hovering over schooling fish, terns make a fast, shallow dive into the school, picking off an individual with their tweezer-like bills.

Species descriptions:

(some of these species are found on the Bank at all seasons while others are only seasonal- this can be very useful when identifying members of this very diverse family)

Greater black-backed gulls, Larus marinus, are found only in the North Atlantic and are the largest gull on earth (30” or 76 cm and a five foot wingspan). Their crisp black and white plumage and sheer size distinguish them from all other birds on Stellwagen. Their massive yellow bills can be used to delicately open shellfish or bluntly kill smaller birds and large fish. They are not as numerous as herring gulls but can be found at all times of the year and in good numbers. They are often found in association (even while nesting) with herring gulls and will displace these smaller gulls while feeding on choice items.

Like herring gulls, adult black-backed gulls look quite similar in winter

and summer. Adult birds in winter have a light speckling of brown about the head. Young birds can often be distinguished from young herring gulls by their more massive and darker bills.

Herring gulls, Larus argentatus, (25” or 64 cm) may be the most commonly seen birds on the Bank at any season. Adults are bright white below with a medium gray mantle and black wing tips spotted with white windows. Their feet are dull pink, bill is yellow with a bright red spot on the lower mandible. Immature birds, in their mottled brown plumage, can easily be confused with other young gulls. Like the black-backed, these gulls take four years to reach adult plumage.

Herring gulls nest in noisy colonies often mixed with other gulls. While foraging they are quick to take advantage of any situation. A gull that falls from the air to pluck a fish from a feeding whale is a very conspicuous sight and soon draws a mob of other hungry birds. They can be found foraging in almost any habitat, from cities to the open ocean. Immature herring gulls are one of the most common birds to be found alongside feeding whales.

Laughing gulls, Larus atricilla, are the smallest of the gulls on the Bank in summer (16” or 41 cm). Their distinctive summer plumage and raucous call makes them easy to pick out of a crowd of gulls and terns. Their dark gray backs are accented by black wing tips and head; the bill, legs and eye ring are a deep, rusty crimson; white “eye lids” ring their dark eyes. In fall, before migrating south, their heads turn white with a pale “ear spot,” their feet and bills turn black.

Like other gulls, laughing gulls can take advantage of any opportunity while feeding: following hunting whales or attending horseshoe crab breeding beaches for eggs. More often though, these gulls hunt small, surface living fish, like sand lance, by making shallow dips to the surface. They may nest in colonies alongside gulls or terns. Their young are vulnerable to attacks from larger gulls and laughing gulls may take very young tern chicks. There does seem to be a balance though: laughing gulls are very wary of, and aggressive towards any intruders so neighbors may benefit from their presence.

Bonaparte’s gulls, Larus philadelphia, are somewhat smaller and more delicate than laughing gulls (13” or 34 cm). Their bills are small and pointed; their wings are pale gray with a triangle of white and tipped with black; their feet are bright red. They have a conspicuous black ear spot in winter (they have black heads in summer). Their flight is less buoyant than other gulls and more like that of a tern.

In fall, as laughing gulls begin to depart, Bonaparte’s gulls begin to arrive from their breeding grounds of the Canadian Plains and Arctic. On the winter feeding grounds of the coasts and open seas, Bonaparte’s hunt in small parties for surface fish and large plankton.

Black-legged kittiwakes, Rissa tridactyla, are another winter gull on the Bank. Tridactyla refers to the absence of the hallux on their feet; they have only three toes. Their flight is buoyant despite their fast, shallow wing beats. About the size of a laughing gull, adult kittiwakes in winter have a short, yellow bill; pale gray mantle and black wing tips; a gray smudge at the nape. First year birds in winter are quite different. Their bills are black and they have a conspicuous band of black on their shoulders and the tip of the tail.

After leaving their nesting cliffs from Newfoundland north, kittiwakes head out to sea to forage for the winter. New Englanders once called them winter gulls as they herald the arrival of the marine winter. Out at sea they may follow fishing vessels or whales but, more commonly, are found in loose flocks hunting small fish or collecting large plankton.

Less common but also seen: Iceland gulls in winter (like the herring gull but has bright pink feet and yellow eyes); glaucous gulls in winter (like the herring gull but much larger, with paler mantle and no black on wing tips); ring-billed gulls in winter – black ring on bill, pink feet and usually found close to shore; Sabine’s gull uncommon in fall and spring – a small gull with tricolored wings.

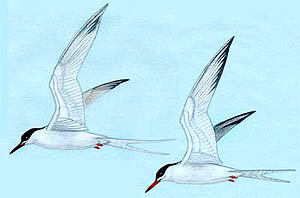

Common terns, Sterna hirundo, are certainly the most numerous of the terns in our area. Like most terns, they have long pointed wings and long tail feathers for a fast maneuverable flight. In summer, commons have a pale gray mantle, black cap, red bill and feet and black tipped wings. They nest on quiet, sandy beaches in large colonies that are very sensitive to the presence of humans. Throughout the day they make trips out to feeding grounds to hunt for small fish like herring and sand lance. Clouds of common terns may be found following the course of large predatory fish, taking advantage of the small fish driven to the surface. Their noisy, cricket like call keeps families together in late summer as the young learn to hunt. Out on Stellwagen they are often heard before seen. Between bouts of hunting, they may rest on the buoys of lobster trawls.

Roseate tern and common tern in summer

Roseate terns, Sterna dougallii, can be found mixed in with a flock of common terns. Unfortunately, their appearance is also quite similar. In summer, roseate terns usually have an all black bill, less black on wing tips and longer tail feathers (characteristics not easily recognized as the bird speeds by at 40 mph). Their call, a mellow, chi-vic, is quite distinctive though from the piercing kee-ahr of the commons.

These terns have been featured on the “right whale license plates” by the Massachusetts Environmental Trust, as one of the rarest animals in the state (the two birds in flight next to the flukes of the right whale. It is not entirely clear why the roseate tern population in North America has been declining but CCS researchers found Cape Cod to be one of the most important habitats for the species in the continent. After nesting and staging in the north, they travel over sea to the West Indies and South America.

Least terns, Stern albifrons, are the smallest members of this family in our area (8-10” or 20-25cm). They are not generally found out on the Bank but may be sighted while leaving from ports surrounded by dunes. They nest in large colonies on islands or peninsulas and hunt in estuaries and other habitats close to shore. They are easily distinguished from the other local terns by their tiny size, yellow bills and complicated face mask.

Very uncommon but also seen: Arctic terns may be seen during their migrations between the Arctic and Antarctic, especially in spring. They are very similar in appearance to the common tern and are best distinguished by their call: a high screeching kip-kip-kip-keahr.

Our Work

Humpback Whale Research

Right Whale Research

Marine Animal Entanglement Response

Marine Geology Department

Water Quality Monitoring Program

Marine Fisheries Research

Seal Research

Shark Research

Marine Education

Interdisciplinary

Marine Debris and Plastics Program

Marine Policy Initiative

Cape Cod Climate Change Collaborative

Publications